RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 12 Issue No: 1 pISSN: 2249-2194

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Dr. Renuka Munshi, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, G building, 5th Floor, T N M C and BYL Nair Children's Hospital, Mumbai Central, Maharashtra, India.

2Department of Clinical Pharmacology, TNMC and BYL Nair Children's Hospital, Mumbai,Central Maharashtra, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Renuka Munshi, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, G building, 5th Floor, T N M C and BYL Nair Children's Hospital, Mumbai Central, Maharashtra, India., Email: renuka.munshi@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: The integration of traditional and complementary medicine with modern healthcare systems has emerged as a significant challenge for numerous countries, driven by the growing popularity of diverse medical practices and the need to control healthcare expenditures. This study endeavours to comprehensively assess Ayurvedic patient care services within a public tertiary care hospital that predominantly delivers modern medicine. Given the escalating recognition of traditional medicine's potential to complement conventional healthcare, understanding the utilization and outcomes of Ayurveda in this context assumes paramount importance.

Methods: A retrospective analysis covering the past five years was performed to investigate the demographics, disease patterns, and use of Ayurvedic treatments among patients receiving care at the hospital. Data on patient retention and the seamless integration of Ayurveda with modern medicine were thoroughly examined.

Result: The study identified a significant rise in the use of Ayurvedic patient care services, predominantly among female patients aged 19-40 years. Over five years, patient retention rates exhibited a gradual increase, signifying a higher level of patient satisfaction and loyalty towards Ayurvedic treatments. Among the ailments treated, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal issues, and dermatological conditions ranked as the most commonly addressed health concerns. Notably, Ayurvedic medicines, in the form of Rasa Aushadhi (herbomineral preparations) emerged as the predominant therapeutic modality.

Conclusion: The study's findings underscore the growing popularity of Ayurvedic patient care services and their potential to complement modern medicine. Effective Ayurveda integration requires understanding patient preferences and disease patterns to optimize healthcare services and bridge the gap between traditional and modern medicine.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

The global healthcare landscape has witnessed a steady rise in the prominence of traditional, alternative, and complementary systems of medicine, both in developing and developed countries. The formal recognition of their significance was underscored at the Alma Ata conference in 1978, with the World Health Organization (WHO) proactively addressing the issue through its Traditional

Medicine Programme since 1976. These systems of medicine have already established a substantial role in delivering healthcare services worldwide.1,2

Due to the growing popularity of diverse medical systems and the necessity to control healthcare expenses, numerous countries are currently incorporating traditional and complementary medicines into their healthcare systems. In certain countries, traditional and indigenous systems have been implemented in parallel with modern medicine in the National healthcare system.3

The healthcare landscape in India is undergoing a progressive transformation, with a growing emphasis on the development of healthcare services.4 Among the Indian systems of medicine, Ayurveda plays a pivotal role in addressing the healthcare needs of a substantial portion of the population.5 Over time, Ayurveda has been officially institutionalized in modern India, with the establishment of formal education and service delivery structures at both central and state levels.6,7 The National Population Policy of 2000 has provided additional support and promotion to the Indian systems of medicine, recommending their integration into the National family welfare program.8

Given the exponential rise in lifestyle-related disorders, the documentation and validation of Indian traditional knowledge, particularly the Indian systems of medicine, has become crucial to prevent their erosion over time or appropriation.9,10 Integrating Ayurvedic principles with modern medicine fosters a holistic approach towards patient care, targeting not only the symptoms but also the underlying causes of illness. Understanding the effectiveness of Ayurvedic practices in contemporary hospital settings promotes patient-centered care, enabling tailored treatment plans that align with individual needs and preferences. Since 2001, our hospital, a tertiary care public teaching institution specializing in allopathic medicine, has been at the forefront of offering Ayurvedic outpatient care services.

Study Aim

This study aimed to comprehensively assess Ayurvedic patient care services within a public modern medicine tertiary care hospital, facilitating the gathering of empirical data on the effectiveness of Ayurvedic therapy in a modern healthcare setting, thus contributing to evidence-based practice and guiding future healthcare policies.

Material and Methods

Study design: Secondary analysis of Outpatient Department (OPD) case records

Setting: Ayurveda OPD of a public-sector tertiary care hospital offering modern medicine, attached to a teaching medical college. The Ayurveda OPD caters to a substantial number of patients each year and provides Ayurvedic medicines free of charge.

Data source: A prospective identification of cases was performed by conducting a thorough manual review of patient records and extracting relevant data from the available case record proformas at the department. The data covered the period from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2022. A detailed medical history, provisional diagnosis, and treatment plan have been maintained in the OPD case files for each patient. In case of multiple ailments, the primary diagnosis was recorded first. Only the primary diagnosis has been included for analysis. The diagnosis was formulated through a comprehensive process involving both clinical examination and laboratory assessment. The clinical examination encompassed a thorough evaluation of the patient's medical history, including current complaints and family medical history, as well as the Astavidh Pariksha (eight-point examination) and Nadi Pariksha (pulse examination). Laboratory assessment encompassed a range of tests, including hematology, liver and renal function tests, lipid profile, C-reactive protein (CRP), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) factor, as well as imaging studies such as X-ray, CT scan, or MRI as per the patient needs.

The diagnosis in Ayurveda was matched with corresponding medical condition in modern medicine. This dual-diagnosis approach enables more comprehensive treatment by integrating both Ayurvedic and modern medical perspectives. Combining the insights gained from Ayurvedic diagnosis, which considers factors such as dosha imbalance and individual constitution, with objective data obtained from modern diagnostic tests helped healthcare providers to develop treatment plans that addressed the root cause of the illness, while also tackling symptoms and imbalances identified through modern medical evaluation.

Data retrieval: A total of 1107 unique new patients visited the Ayurveda OPD during the specified timeframe, accounting for 3626 total visits. However, records for 26 patients were either in an unrecordable format or incomplete, preventing their inclusion in the analysis. As a result, a final sample of 1084 patients with 3600 visits over five years was considered for the study. After a rigorous screening process, a total of 1039 patient records were deemed eligible for Prakriti analysis. Additionally, 1015 patient records were included in the study of various medicine dosage forms used. Furthermore, 1857 visit records were examined to determine the frequency of commonly used Ayurvedic medicines within the OPD setting. Among the 1015 patients, 83.04% (853 individuals) were also receiving allopathic treatment for various systemic conditions such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hypertension, and bronchial asthma, among others, in addition to ayurvedic treatment.

Data collection and demographic data: The data collected comprised socio-demographic details, Ashtavidha Pariksha, Prakriti assessment, dietary habits, working conditions, Strotas, and diagnosis utilizing an Ayurvedic case record form developed by the department.

Ethics: The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee [Project No. ECARP/2023/83]. The request for a waiver of consent was granted as this was a secondary analysis of data, and all patient records were assigned a Unique Identifier Number (UIN) to maintain confidentiality and anonymity.

Statistical analysis: Data entry and organization were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010, while descriptive statistics were employed for data analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 1,084 distinct individuals sought treatment at the Ayurvedic OPD between 2018 and 2022, of whom 680 (63%) were women and 404 (37%) were men. Gender distribution trends over the years have consistently demonstrated a predominance of female patients attending the OPD. Notably, there was a decline in outpatient department (OPD) visits during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021); however, the numbers gradually rebounded in 2022.

Age distribution

Analysis of age distribution revealed interesting trends among patients seeking Ayurvedic services. Notably, patients aged between 41 and 60 years made up the majority, accounting for 2,029 visits (405.8±162.44), followed by patients in the age group of 19-40 years with 992 visits (198.4±124.98), while the 61-75 years age cohort made 412 visits (82.4±27.79). On the other hand, patients between 13 and 18 years of age accounted for 77 visits (15.4±5.21), and those in the age groups of 0-12 years and above 75 years constituted 45 visits (9±2.68) (9±3.32), respectively.

Details of the overall patient visits and retention from 2018 to 2022 are given below and summarised in Table 1.

- New patient trends: The number of new patients peaked in 2019 (338) but dropped significantly in 2020 (104) due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Subsequently, there was a gradual increase in 2021 (153) and 2022 (162).

- Total visits: The total number of visits reached its highest in 2019 (1,231). However, in 2020, visits sharply declined (379) due to the pandemic. Visits rebounded in 2021 (497) and 2022 (725).

- 5-year cumulative visits of new patients: The cumulative visits of new patients showed a steady growth in 2018 and 2019, but dropped to 215 in 2020. The trend improved in 2021 (544) and 2022 (411).

- 5-year average patient retention: Average patient retention varied across the years, with the highest observed in 2022 (411 visits).

- Percentage average patient retention for 5 years: The percentage representation of average patient retention shows the proportion of retained visits compared to the initial visits over a five-year period. It was observed that the percentage retention fluctuated over the years, with the highest retention noted in 2022 (253.7% of initial visits).

- Percentage 5 years retention from new patients: The percentage of patients retained over five years from the pool of new patients each year showed that 20% of new patients in 2018 were retained for the entire five-year period, followed by 25% in 2019, 33.33% in 2020, 50% in 2021 and 100% in 2022.

- Percentage year-wise 5th year retention rate: The retention rate for patients who began treatment in 2018 and continued for five years was 31.4%. The retention rate for patients who started in 2019 for the f ifth year was 24.8%, while it was 18.9%, 54.7%, and 56.7% for the years 2020, 2021 and 2022, respectively [Table 1].

Distribution based on Pradhan Prakriti

Distribution of patients based on Pradhan Prakriti (dominant body constitution) showed that Pitta Pradhan (Pitta dominant) accounted for 38% (393) of the total 1039 patients, followed by Vata Pradhan (Vata dominant) representing 37% (385), and Kapha Pradhan (Kapha dominant) constituting 25% (261). Prakriti assessment was done as per the proforma developed by the Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha (CCRAS).11

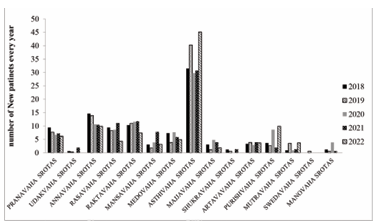

According to the Ayurvedic Strotas system, diseases encountered in the Ayurveda OPD can be classified into 15 systemic categories. The percentage of newly diagnosed patients in the Pranavaha Strota remained relatively stable over the years, with minor fluctuations ranging from 6.17% to 9.48%. Conversely, the Udakavaha Strotas consistently had a low number of diagnosed patients, with a slight increase (1.96%) noted only in 2021. The Annavaha Strotas showed a declining trend, with the percentage decreasing from 18.33% in 2016 to 9.88% in 2022. Similarly, the Rasavaha Strota exhibited fluctuating percentages, reaching a peak of 13.8% in 2016 and dropping to a low of 4.32% in 2022. On the other hand, the Raktavaha Strotas demonstrated relatively stable percentages, ranging from 10.4% to 12.05% over the years. In contrast, the Asthivaha Strotas displayed fluctuating percentages, with the highest percentage of 45.06% recorded in 2022. As for the remaining Strotas (Mansavaha, Medovaha, Majjavaha, Shukravaha, Artavavaha, Purishvaha, Mutravaha, Swedavaha, and Manovaha), The proportion of newly diagnosed patients has remained consistently low over the years. [Figure 1].

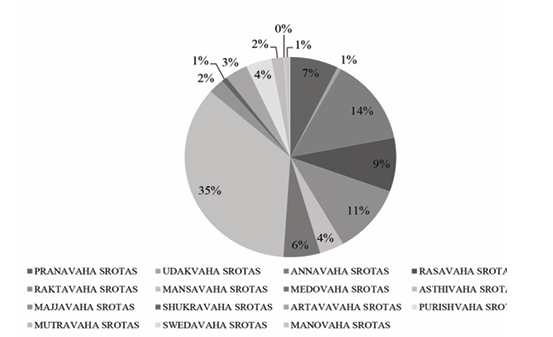

The distribution of unique patients across different Srotas (channels) in the study was analyzed, with a total of 1,084 patients included in the analysis. The findings revealed variations in patient distribution among the Srotas. Pranavahastrotas accounted for 7.19% (n=85) of the total patients, while Udakavahastrotas represented 0.57% (n=6). Annavahastrotas had the highest number of unique patients, with 138 individuals (13.75%). Rasa vahastrotas accounted for 8.45% (n=92), Raktavahas trotas for 10.94% (n=113), Mansvahastrotas for 3.69% (n=37), and Medovahastrotas for 5.49% (n=62). The highest number of patients was observed in Asthivahas trotas, with 390 (34.64%) unique patients. Majjavahastrotas accounted for 2.39% (n=28), Shukravahastrotas for 0.82% (n=8), Artavavahastrotas for 3.43% (n=39), Purishvahastrotas for 3.88% (n=49), Mutravahastrotas for 1.84% (n=24), Swedavahastrotas for 0.09% (n=2), and Manovahastrotas for 0.91% (n=11).

Distribution of patients among Srotas

Review of the distribution of unique patients among different Srotas (channels) demonstrated that Asthivahasrotas had the highest number of unique patients, comprising 34.64% (390), followed by Annavahasrotas with 13.75% (138), Raktavahasrotas with 10.94% (113), Rasavahastrotas with 8.45% (92) and Pranavahastrotas with 7.19% (85). Conversely, Udakavahasrotas had the lowest number of diagnosed patients i.e., 0.57% [Figure 2].

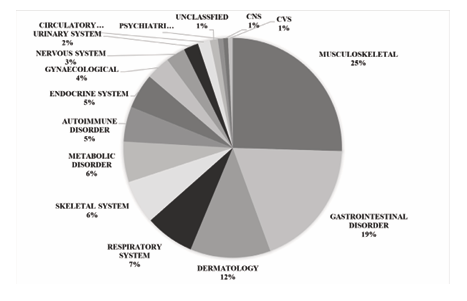

Systemic classification of diseases

Ayurvedic OPD encounters a wide range of diseases, which can be categorized into 16 systemic categories based on modern body systems. The most prevalent diseases were from the musculoskeletal system (24.8%), followed by gastrointestinal tract (GIT) disorders (18.4%), and dermatological conditions (11.7%) [Figure 3].

Commonly observed diseases in the OPD

Among the different cases presenting in the Ayurved OPD, 57.59% (417) cases belonged to the top five most widely presenting diseases. Osteoarthritis (Sandhigat Vata) was the most prevalent disease, accounting for 33.7% (244) of the cases, followed by rheumatoid arthritis (Aamvaat) at 7.2% (52), hyperacidity (Amlapitta) at 6.6% (48), obesity (Sthoulya) at 6.2% (45), and haemorrhoids (Arsha) at 3.9% (28). Sandhigat Vata, and Aamvaat, belong to the Vata rogadhikara, while Amlapitta, and Arsha belong to the Pitta rogadhikara categories of Ayurvedic diseases. Sthoulya is Kapha Rogadhikara disease.

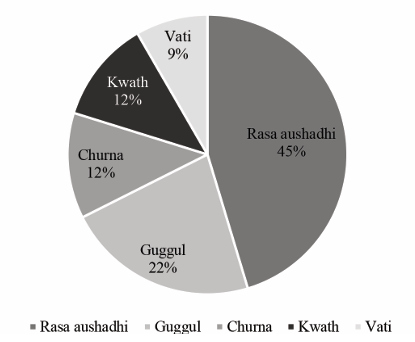

Ayurvedic medicine usage

Rasa Aushadhi (herbo-mineral preparations) emerged as the most commonly used form of medicine, accounting for 45.34% (842) of the total average usage. Guggul (resin-based formulations) and Churna (powders) were also frequently used, comprising 22.24% (413), and 12.22% (227), respectively. Kwath (decoctions) and Vati (tablets) were among the other commonly utilized medicine forms, constituting 11.85% (155), and 8.35% (155) of the total usage, respectively [Figure 4].

Further analysis showed that within the Rasa Aushadhi category, Sutshekhar Ras was the most frequently used medicine, accounting for 13.2% (245) of the total usage and primarily employed in the treatment of hyperacidity. Among the Guggul formulations, Sinhnad Guggul was commonly prescribed for Amavata (5.24%), while Gokshuradi Guggul was used in the management of urinary tract infection/Prameha and Shoth (edema) (4.72%). Avipattikar Churna (4.3%, n=80) and

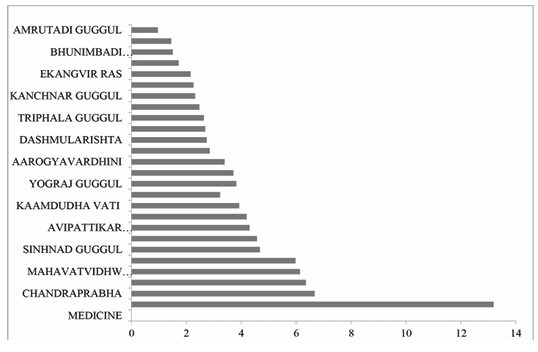

Maharasnadi Kadha (2.9%, n=53) were prominent among the Churna and Kwath categories, respectively, with Avipattikar Churna used to treat hyperacidity and Maharasnadi Kadha utilized for joint pain and Amavata. Notably, Kaamdudha Vati (3.9%, n=73) emerged as the most commonly prescribed tablet formulation, primarily for hyperacidity [Figure 5].

Discussion

Chronic diseases have emerged as a significant health challenge, affecting both developing and developed countries, which, if not effectively addressed, could place an immense burden on the global healthcare systems.12 Regrettably, chronic diseases like cancer, cardiac disorders, diabetes, and degenerative bone disorders are inherently challenging to treat, leaving patients with limited options.13,14 In light of these circumstances, the integration of Ayurveda with allopathic medicine has emerged as a promising healthcare approach, offering patients the combined benefits of traditional and modern systems, particularly for managing chronic illnesses.15-17 This preference for natural products and conventional medicine is reflected in global healthcare practices, with approximately 80% of the population relying on such systems for their healthcare needs.18,19 Factors such as concerns over chemical-based products, cost of modern medicines, and dissatisfaction with allopathic treatments contribute to this growing trend.20-23

A comprehensive assessment of Ayurvedic patient care services in a tertiary care hospital has provided valuable insights into the utilization and demographics of outpatient services.

An examination of the age distribution of patients seeking Ayurvedic services revealed a notable demand for Ayurvedic care among individuals aged 19-40 and 41-60, who consistently accounted for the highest number of visits during the observed period. Understanding the factors contributing to the variation in service utilization across different age groups and identifying potential barriers may prove crucial in tailoring outreach efforts and improving accessibility to Ayurvedic treatments for all age cohorts.

The study also analyzed patient retention rates in the context of Ayurvedic patient care services over five years. Our findings revealed a steady rise in patient retention, suggesting an encouraging trend of growing patient satisfaction and loyalty towards Ayurvedic healthcare. Specifically, the retention rates escalated significantly, starting from 20% in 2018 and eventually reaching a remarkable 100% by 2022. These results underscore the effectiveness and appeal of Ayurvedic treatment modalities, fostering strong patient-provider relationships and enhancing long-term patient engagement.

The study discussed the significant role of Srotovijnana (knowledge of channels), which focuses on the understanding of channels within the human body, in Ayurvedic biology. The distribution of patients across different Srotas was analyzed to gain valuable insights into the relative prevalence of diseases and to better understand trends within specific categories. Our research revealed that the Asthivahastrota had the highest number of patients, followed by the Annavahastrota, while Udakavahastrota, Shukravahastrota, Swedavahastrota, and Manovahastrota had relatively lower patient counts.

The modern classification of the healthcare system aligns with Ayurvedic Strota's findings, with disorders of the musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and dermatological systems showing the highest patient count. Specifically, osteoarthritis (Sandhigata Vata), rheumatoid arthritis (Amavata), acid hypersecretion (Amlapitta), obesity (Sthoulya), and haemorrhoids (Arsha) were the most prevalent diseases within these categories. The study findings align with Ayurveda's traditional strengths in managing musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and dermatological conditions, which are often slow to respond to conventional treatments, leading patients to prefer Ayurvedic care. Published literature supports the effectiveness of Ayurvedic remedies for joint disorders such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and lower back pain.24-27

The concept of Prakriti, referring to an individual's unique biological specificity resulting from cellular and genomic peculiarities, plays a crucial role in personalized healthcare interventions in Ayurveda. The interactions between Vata, Pitta, and Kapha doshas shape an individual's dominant Prakriti, allowing customized treatments to address specific imbalances. Studies have shown associations between Prakriti types and disease susceptibility, treatment response, and overall wellbeing, supporting Ayurveda's goal of promoting optimal health and disease prevention.28,29

Our findings also demonstrated a preference for Rasa Aushadhi formulations, suggesting their perceived effectiveness and acceptance among patients. The prominence of Sutshekhar Ras highlights the prevalence of hyperacidity-related complaints in the patient population. The utilization of Chandraprabha vati and Agnitundivati for specific indications aligns with the targeted approach of Ayurvedic medicine.

A significant number of patients visited the Ayurvedic OPD, particularly when experiencing limited relief or encountering side effects such as gastritis from allopathic interventions. Osteoarthritis was one such condition for which the Ayurvedic OPD received numerous patients seeking alternative options due to the lack of relief or adverse effects from conventional treatments. Allopathic medicine may be more suitable for acute conditions, infectious diseases, and surgery, while Ayurveda's focus on lifestyle, diet, and medication makes it a practical choice for managing chronic disorders.30

Our study thus provides valuable insights into the utilization and distribution of Ayurvedic patient care services in a modern medicine public tertiary care hospital and aligning disease trends with Ayurveda's traditional strengths. The consistent upward trend in patient visits and overall patient retention over the years indicates a positive impact and increased trust in Ayurvedic treatments among patients. Previous studies have also demonstrated that people have faith in traditional systems of medicine, supporting the potential for AYUSH clinics to complement existing healthcare services.

Limitations

Despite the valuable insights gained, this study has certain limitations. The retrospective nature of the data collection may result in incomplete or missing information in patient records. Additionally, the study was conducted at a single tertiary care hospital, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other settings. Future studies with larger sample sizes and multi-center designs could further validate and expand on these results.

Conclusion

The valuable insights gained from this research have the potential to shape healthcare policies, improve patient care, and encourage the integration of Ayurveda as a complementary and integral part of mainstream healthcare practices.

Financial support and sponsorship:

Nil

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Financial support NIL

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Narendra Kotwal, Dr. Pallavi Dhupe, and Dr. Dipti Kumbhar for their technical insights in this study.

Supporting File

References

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978. www.who.int

- World Health Organization. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002-2005 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002 [cited 05 January 2025]. Available https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ WHO-EDM-TRM-2002.1

- Bodeker G, Ong CK, Grundy C, et al. WHO global atlas of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine. Kobe, Japan: WHO Centre for Health Development; 2005. Available from: https://iris. who.int/handle/10665/43108

- Government of India. National Health Policy 2017. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India; 2017 [cited 05 January 2025]. Available from: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/ f iles/9147562941489753121.pdf

- Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Mainstreaming of Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy with the health care delivery system in India. J Tradit Complement Med 2015;5(2):116-8.

- Patwardhan B. Traditional medicine: Modern approach for affordable global health. In: Commission on Intellectual Property Rights IaPHC. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2005. www.who.int

- Patwardhan K, Patwardhan B. Ayurveda education reforms in India. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2017 Apr-Jun;8(2):59-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2017.05.001. Epub 2017 Jun 7. PMID: 28600165; PMCID: PMC5496999.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Population Policy 2000 [Internet]. New Delhi: Government of India; 2000 [cited 05 January 2025]. Available from: https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/ files/2021-07/7%20National%20Population%20 Policy%202000.pdf

- Mukherjee PK, Harwansh RK, Bahadur S, et al. Evidence based validation of Indian traditional med icine - Way forward. World Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2016;2(1):48-61.

- Jaiswal, Y. S., & Williams, L. L. (2017). A glimpse of Ayurveda: The forgotten history and principles of Indian traditional medicine. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 7(1), 50–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.02.002

- Lavekar GS. Case report form for determination of prakriti. In: Lavekar GS & Padhi MM (Editors). Clinical research protocols for traditional Health sciences. New Delhi: Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha; 2010. p. 1073-1082.

- Choi BCK, McQueen DV, Puska P, et al. Enhancing global capacity in the surveillance, prevention, and control of chronic diseases: seven themes to consider and build upon. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62(5):391-7.

- Hacker K. The burden of chronic disease. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2024;8(1):112-119.

- Brown A, Hayden S, Klingman K, et al. Managing uncertainty in chronic illness from patient perspectives. Journal of Excellence in Nursing and Health care Practice 2020;2:1-16.

- Gupta, R. Integrating Ayurveda with modern medicine for enhanced patient care- analysis of realities. The Physician 2024;9(1):1-6.

- Javed D, Dixit AK, Anwar S, et al. Exploring the integration of AYUSH systems with modern medi cine: Benefits, challenges, areas, and recommenda tions for future research and action. Journal of Primary Care Specialties 2024;5(1):11-15.

- Mortada EM. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine in current medical practice. Cureus 2024;16(1):e52041.

- Yuan H, Ma Q, Ye L, et al. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Mole cules 2016;21(5):559.

- Patwardhan B. Bridging Ayurveda with evidence-based scientific approaches in medicine. EP MAJ 2014;5(1):19.

- Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study. JAMA 1998;279(19):1548 1553.

- Siahpush M. Postmodern values, dissatisfaction with conventional medicine and popularity of alternative therapies. J Sociol 1998;34(1):58-70.

- Welz AN, Emberger-Klein A, Menrad K. Why people use herbal medicine: insights from a focus-group study in Germany. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018;18(1):92.

- Misra R, Singh S, Mahajan R. An analysis on consumer preference of Ayurvedic products in Indian market. Int J Asian Bus Inf Manag 2020;11(4):1-15.

- Kessler CS, Pinders L, Michalsen A, et al. Ayurvedic interventions for osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 2015;35(2):211 32.

- Chopra A, Saluja M, Tillu G, et al. Ayurvedic med icine offers a good alternative to glucosamine and celecoxib in the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, controlled equivalence drug trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(8):1408-17.

- Park J, Ernst E. Ayurvedic medicine for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2005;34(5):705-13.

- Kumar S, Rampp T, Kessler C, et al. Effectiveness of Ayurvedic massage (Sahacharadi Taila) in patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med 2017;23(2):109-115.

- Dey S, Pahwa P. Prakriti and its associations with metabolism, chronic diseases, and genotypes: Possibilities of newborn screening and a lifetime of personalized prevention. J Ayurveda Integr Med 2014;5(1):15-24.

- Chatterjee B, Pancholi J. Prakriti-based medicine: A step towards personalized medicine. Ayu 2011;32(2):141-6.

- Sureka, R. K., & Srivastava, S. (2024). Efficacy of Ayurveda in the prevention of lifestyle diseases or non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Journal of Ayurveda and Integrated Medical Sciences, 9(8). https://doi.org/10.21760/jaims.9.8.18